Homily for the Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time (September 12 & 13, 2020)

How often must I forgive?

--I say to you, not seven times but seventy-seven times.

During the pandemic this year, I’ve been quarantined at home with my family, like many of you. I am married and the father of four young children all four years old or younger. In one of our rare bits of free time, my wife and I watched the musical Hamilton, which was released on TV around the 4th of July.

I see this musical as very timely for our current moment in history and for our Gospel reading in which Christ calls us to limitless forgiveness and mercy for our brothers and sisters. Let me describe a climactic scene to you from the musical.

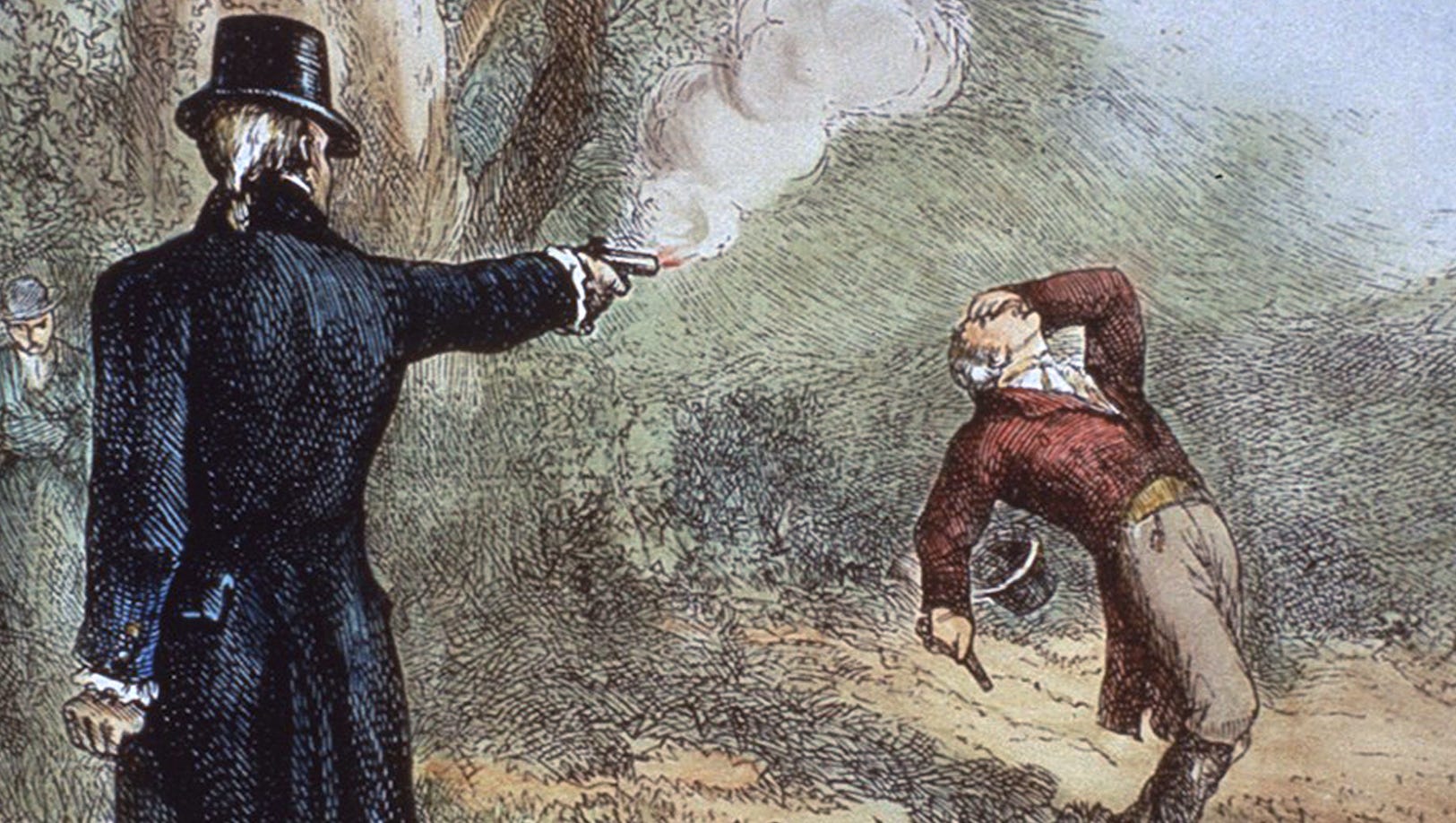

Two men stand ten paces across from each other, each pointing a dueling pistol at the other. They are in a the midst of a wooded ledge overlooking the Hudson River. It is dawn and the sun is shining on the water and Manhattan on the opposite shore.

The two men are Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. They could be brothers. Both were renowned, rising scholars at King’s College, and key young officers in the Continental Army. Both have outsized political ambitions, hoping one day to replace George Washington as the President of the Republic.

The two almost-brothers are on a collision course. Their rivalry consumes them both, breeding envy and resentment in each. They begin to embody the language of our first reading, “Wrath and anger are hateful things, yet the sinner hugs them tight.” Burr believes Hamilton deliberately thwarts him at every turn and takes each position that Burr believes that he was born to. Leading them both this climax: Burr and Hamilton in a duel of drawn pistols.

I believe that our country currently finds itself locked into a duel to the death like the climax of Hamilton. We are consumed by our own profound senses of envy, grievance, resentment and rage, much like the feelings that destroyed these two Founding Fathers.

Perhaps thinking of a long running conflict like Aaron Burr’s and our own, Peter asks, “Lord how many times must I forgive my brother?” Peter gives a generous starting offer: is seven times enough? That is probably more than we would extend to most people outside of our family. Conventional wisdom says, “fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.” Meaning that we should cut people off after the first offence. If someone hurts us after that first time, we have no one to blame but ourselves. If it happens a third time, it’s time to pick up the dueling pistols. By this measure, Peter’s offer marks him as a kind of sucker or glutton for punishment.

Jesus’ response, then, should astonish us. Not seven, he says, but 77 times. In the symbolic language of Scripture this means a limitless number of times. How is that humanly possible?

[Pause for a transition]. I was on a long car ride with a friend two or three years ago. This friend went to Bellarmine with me and is a frequent workout partner. He grew up in a rural part of the state, an upbringing quite different from mine. Most of his family still lives in out in the country. I, on the other hand, am very much a city boy. I really have no sense of Kentucky geography outside of the city and am the product of an urban upbringing and worldview.

We started talking politics and he really surprised me. I was completely floored by the amount of anger he felt towards our country’s leadership and elites. He felt like he and his family were completely ignored, looked down on, or despised by American society. To put it another way, he felt like his life did not matter in their eyes.

When I think of our country’s divisions, I think of him. We are living in a time when we don’t want to even listen to people who are different from us, much less have mercy on them or ask them to have mercy on us. I asked a few minutes ago how it is humanly possible to forgive a limitless number of times, as Jesus commands.

Surely, the human divisions that we have created can be dismantled by human actions. We created this mess, surely we can fix it, right? I have bad news. The answer is no. Our sinfulness is greater than our own ability to fix it. Our wrath is greater than our ability to forgive. It is not humanly possible.

And so in Jesus’ parable today, we should cast ourselves in the role of the indebted servant. This man owes a huge, unbearable sum to the king. The literal meaning of his debt is “ten thousand talents” an impossibly onerous debt beyond the ability of a person to repay in a lifetime. Note that Jesus often uses the metaphor of owing money to being in debt spiritually: that is, being enslaved to sin and evil and unable to escape it.

In the parable, the servants’ plea, “be patient with me, and I will pay you back in full” is an empty promise. And yet, the king is moved with compassion and fully forgives the debt, wiping his account clean, releasing him from a future of poverty and slavery for himself, his wife, and his children.

You see despite the bad news there is even better good news, and surely you know this. The grace of God is greater than our sin. The mercy of God is more powerful than our grievances. When we are able to forgive our brother and our sister, it is because God is there, working His grace and mercy through us, and making us merciful, like the Father.

As Jesus asks us, “Should we not have had pity on our brother and our sister,

as our Lord God had pity on us?”

In the end, the mercy of God allows us to enter into the Wedding Feast of the Lamb, where Hamilton and Burr have laid down their arms, and all have been transformed by grace.

Comments

Post a Comment